- Home

- Jacob Rosenberg

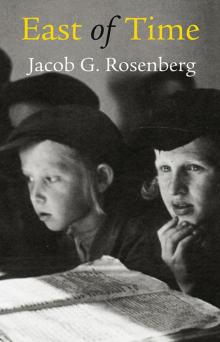

East of Time Page 15

East of Time Read online

Page 15

There is a time for everything,

and a season for every purpose under heaven:

A time to be born and a time to die,

A time to plant and a time to uproot,

A time to kill and a time to heal,

A time to destroy and a time to build,

A time to weep and a time to laugh,

A time to mourn and a time to dance,

A time to cast stones and a time to gather them,

A time to embrace and a time to refrain,

A time to search and a time to give up,

A time to keep and a time to discard,

A time to tear and a time to mend,

A time to be silent and a time to speak,

A time to love and a time to hate,

A time for war and a time for peace.

And as an afterthought, he added: ‘In peace we prepare for war, and in war for another war. Madness has no seasons.’

Metamorphosis

Gerhard Reimer was born in the deep north-east, beyond the Gulf of Riga, where moons like lost yellow ships anxiously searched the interminable oceanic expanse of black skies for a secure port of call.

When he was eight his father, Herman Reimer, sent him away to a boarding school in Tallinn, where he was taught many useful things: mastery of the German tongue, discipline, songs, and nightly drillings. ‘Don’t saunter!’ his marching instructor shouted. ‘Saunterers think. Soldiers shouldn’t!’ Although little Gerhard was always thinking — for he was intelligent and perceptive — he nevertheless had no problem obeying his new teachers. Obedience had been an integral part of his strict upbringing.

Gerhard grew into an exceptionally handsome young man. At twenty-one he was an upright Christian, and a decorated leader of the Hitler Youth. He wore shiny black boots, a brown shirt, and a red armband adorned with a black cross bent into hooks (at times he wondered how Jesus would have looked on a cross like that). He still hadn’t forgotten those fearful nights when he heard Mama in the adjoining room grappling with Papa in their bed; and how one frosty winter’s night he, little Gerhard, had crawled out of his own warm bed and knelt before the crucifix on the wall, praying that his father might show his mother some mercy.

One morning in December 1942, when the earth was painted with a coat of snowflakes, there was a knock on the door of Gerhard’s comfortable apartment, which had belonged to a Jewish doctor who had been sent away. Clicking his heels and calling Heil Hitler!, he jumped to attention before the two uniformed officers, who politely but curtly asked him to hop into the car waiting outside.

They journeyed for hours without exchanging a word. Gerhard didn’t mind, he was used to war games and secret missions. Gazing out languidly at the snowy Christmas landscape hurtling past, he dozed off, and all at once he could hear his parents in their bed again, and mother’s whimpers and pleas, and he saw his homely cloud-streaked moon, but this time it was poking out at him an enormous slimy red tongue...

They arrived mid-morning and were greeted subserviently by an elderly gentleman. On his nose rested a pair of brown horn-rimmed spectacles; he wore a grey hat, a black-and-white herringbone coat — and a yellow star on his chest! ‘What’s this?’ cried Gerhard, reaching for his scout knife. ‘Are there still Jews left in our new Reich?’

‘Hold it, hold it!’ commanded his humourless escort. He relieved Gerhard of his weapon. ‘From now on,’ he said, ‘you will do as this man tells you.’

‘But why?’ Gerhard shouted in desperation. ‘Please, it’s all a big mistake — what have I to do with these people?’

‘You’ll have to ask your grandfather’s father,’ responded one of the escorts. They jumped into the car and drove off in a cloud of dust.

Two Jewish policemen respectfully chaperoned Gerhard to his new quarters, where he threw himself on the cold bunk and cursed, screamed, wept, and perhaps thought of escaping. But the habit of obedience would not permit him even now to rebel against authority, and after a month or two of self-isolation Gerhard bowed his head before the Eldest, the man with the yellow star who had welcomed him, and embarked on his career as a weaver in Kaszub’s textile factory.

At first he was rather confused. He had never seen Jews like this — gaunt, haggard, yet upright and proud Jews, some of them even good-looking. Even their noses looked normal! Oh, heavens, they must all be like me, he thought, neither Gentile nor Jew. And there behind one of the huge machines he spotted my former school friend — petite, dark-eyed, with waves of shoulder-length auburn hair — the beautiful Debora, whose white skin would have been the envy of many a fine Aryan lady. Was she Jewish too? He soon found himself wondering what she thought of him. And so, after days of curiously searching each other’s faces, there began to grow a longing for words, and then for the touch of hands.

Gerhard took a strong liking to Debora’s wise father, David Wajnberg, who spoke about his Jewish agnosticism with a great deal of pride; who, with reference to many historical examples, pointed out that nations which had oppressed Jews had always written out their own curse; who, despite all the setbacks, believed that the only way for humanity to survive was through socialism. Lying on his bunk at night, Gerhard pondered his life, his flame for Debora, his attachment to her father, the meaning of destiny, and his mysterious bond to these ghetto people of whom he had known so little...

In September 1945, on a sunny morning in Rome, I was strolling near the Piazza d’Espagna when I came upon my old friend Debora. Her face, against the blue Roman sky, looked paler than it really was, and her black eyes much blacker. We practically fell on each other, and stood for a good while locked in a tender embrace. With an almost mischievous smile, she invited me to visit her room.

After an arduous climb up a precipitous winding staircase, we stood in an unlit corridor. I could sense Debora’s tension, and thought I detected the old fire in her eyes as she reached for the key that was hanging on a chain around her neck. Quickly she unlocked the squeaky door, and there — oh, my God, there on an army bunk, white as a ghost, lay Gerhard Reimer! He was somewhat astonished to see me, but his greeting was warm and friendly. We drank hot coffee without exchanging a word. There are times when silence is the most natural condition. When I rose to say goodbye I kissed Debora more fully on the lips than I should have, and noticed the jealous glint in Gerhard’s eyes.

‘Please forgive him for not getting up from the bunk,’ she whispered. ‘He is in agony. You see, it’s just the third day after his circumcision.’

Riddles

My former schoolmate Yossele, who had assisted our sport teacher Laibl Grundman in burying within the schoolyard a list containing the names of all our school’s students, a kind of time-capsule, was a fellow of simple language and complex ideas. Yossele espoused the theory that there were no grey areas in life, everything was either black or white. Outside of that equation, he declared with his characteristic extremity, dwelt only the absurd.

Yossele maintained that the central pillar of our social structure was hypocrisy. Without it our system would collapse, he said, like a house of cards on a windy day. Adam and Eve, he further argued, had sewn leaves together to make not loincloths but masks. Those masks, he proclaimed triumphantly, had transformed the earth into a living paradise!

Yossele was fond and proud of his Yiddish school, which he completed just before the outbreak of the war. His secondary education would be the ghetto, his university Auschwitz, and he would gain his postgraduate credentials from prestigious Bergen-Belsen, with high distinctions in remembering.

I had lost contact with Yossele in 1939, not long before we were all consumed by that cataclysm of blood and fire. It was in New York that I met him again, many years later, in a room full of strangers. He was happy only when he spoke about his miseries: life in camp, the beatings, betrayals, how he was sold for a kilo of sugar, his interrogation by the Gestapo, his escape, the night he spent in a kennel with a dog — probably an angel, he explained.

But when

he spoke of how, one summer’s night, he had been caught by some villagers and hung by his legs from a cherry tree, he just couldn’t stop laughing. People thought he was crazy. What they didn’t realize was that Yossele was reliving his youth.

The Absence

The architects of our inverted state had a tremendous aptitude for social geography: most of the ghettos they established were sheltered from military activities, safe and secure amid a wider populace not averse to lending a hand in the achievement of their masters’ final solution.

My daring street friend Leon Ronski walked about the world with a snub nose, a straw-white mane, and eyes like an unblemished summer sky. One morning he noticed his father — the pious and respected Szachna Ronski, a giant of a man — sitting in a corner and sobbing like a child. ‘He hasn’t eaten for three days,’ Leon’s mother told him. ‘He just can’t bear it any more. I begged him to take my slice of bread, but he’d rather die than do that.’

As soon as dusk fell Leon rushed to the edge of the ghetto, sneaked out through the barbed wire and boarded the last tram to the outskirts of a nearby village, where the granaries were bursting at the seams and virtually every home baked its own bread. He waited until the people were sleeping soundly, took off his shoes, and was about to put his plan into motion when the faithful village dogs picked up the scent of an intruder. Within minutes the whole place was on its feet. Men, women and children ran out into the night, all in their underwear, armed with torches and pitchforks, screaming ‘Żyd, żyd, żyd!’ Leon was caught soon enough, sitting in the branches of a tree he had managed to climb into. Naturally, the honour of dealing with the trespasser was given (principally) to the one who had spotted him first. Fair is fair.

Two days later, battered and bloodied all over, Leon was marched back at gunpoint to the edge of the ghetto. The guards released him and ordered him to run. Then, as he was about to scale the fence, one of them sent a bullet through his head. The Jewish police were told to notify his parents that he had been shot trying to escape from custody.

Just before the news was brought to him, Reb Szachna happened to be studying the Bible, and had reached the twenty-eighth chapter of Genesis. He closed his eyes, reciting verses 20 and 21 from memory:

And Jacob made a vow, saying: ‘If God remains with me, and protects me on this journey that I am making, and gives me bread to eat and clothing to wear, so that I return safe to my father’s house, then the Lord shall be my God.’

Something caused Szachna to open his eyes, and his gaze fell on the open Tanach. He uttered a cry. The two verses that he knew so well were missing, and in their place there gaped an absence as blank as despair.

Rabbi Chaskele

I learnt about Rabbi Chaskele and his fate from the rabbi’s nephew, Kalman, a Talmudist in his own right. While we were queuing for bread early one winter’s morning, the young man, rubbing his frozen hands together and stamping his cold feet, sang an infectious old Yiddish folksong under his breath:

Yidl with his fiddle,

Arieh with his bass,

Life is but a little song,

Why then make a fuss?

I chuckled; we exchanged some words, and soon found ourselves chatting like old friends. Before long Kalman was telling me his story — which I quickly realized was merely a brief shortcut to that of his uncle. ‘I came here from a nearby shtetl,’ he said, ‘where, in a cluster of white houses huddling like forlorn sheep on a piece of land that was once green pasture, lived a few thousand Jews. Their elder, their doyen, was my frail widowed uncle Chaskel the kabbalist, known as “Chaskele” because he was so incredibly tiny. In our time of harsh and bitter realities, Chaskel could withdraw into his own dream world. He had many sayings. “Kalman,” he would tell me, “creation does not exist for its own sake, but for the sake of the shining force of the Creator.” You see, one has to be good to give new meaning to old truths, and my uncle, whom I loved like a father, really was good.’

My new friend paused, drew a deep breath. ‘A day before Purim, two men in black uniforms came to see my uncle. They demanded ten Jews for a Spiel, a ‘show’, to be staged in the marketplace at dawn the next day. Uncle told them that he would be there; the other nine they would have to find for themselves. By way of deposit they gave him a beating, and left. I knew what to expect. All night long I begged him to run for his life but he wouldn’t hear of it. Only frauds, phony leaders, ran away from their communities in times of peril, he said. I argued that there was no logic in his staying. Maybe, he agreed, but too much logic was sometimes tantamount to absurdity! Desperate, infuriated, I cried: “For God’s sake, uncle, what are you trying to achieve?” My uncle nodded. “Yes, Kalman,” he answered, “precisely for God’s sake have I endeavoured, all my life, to instruct men in righteous deeds, not in those that are merely speculative or convenient.” I knew he was right, but how could I let it go at that? “What you say is true,” I told him, “but it has little to do with the grim reality staring you in the face today.” For a good while my uncle, the sharp kabbalist, said nothing. I thought he was about to succumb. Instead, this frail man who fasted every Monday and Thursday pushed his face close to mine and whispered into my ear: “Kalman, my son, the song of light in its dialogue with darkness does not need to authenticate itself in accordance with existing realities.”

‘An eerie dimness hovered over the marketplace on that godforsaken dawn. The whole community, having been ordered to assemble around the gallows, watched anxiously as Rabbi Chaskele emerged from his house. Behind him walked nine elderly Jews, who had spent the night in prayer. They walked firm and upright, their heads held high. “Look, it’s a miracle, a miracle,” someone murmured. “Our Rabbi Chaskele is growing taller every moment! Look, can you see? Soon he’ll reach the heavens!”

‘As a soldier placed the noose around my uncle’s neck, Chaskele whispered, almost plaintively: “Perhaps you will permit me one last wish. I would like to touch the officer in charge.” The soldier laughed. “Why would you want to do that?” he sneered. “I don’t mean any harm, sir,” Chaskele replied. “I just want to ascertain if this man, too, has been created in God’s image.”’

Elegy for a Little House

It stood alone, at 12 Limanowskiego Street, a modest two-storey timber dwelling with four bashful windows, on its pitch-black roof a happy chimney wearing a smoky wig. It looked small beside the neighbouring four-storey block where I lived. Yet it housed four families, each behind a friendly open door. Upstairs was a glazier with his diminutive wife and five children; next to them, a widowed cobbler with a daughter and a son, the boy unable to speak because he was born with a split on his upper lip. The ground floor was occupied by Noah the baker, whose wife had borne him three daughters and three sons, all master bakers; and across the unlit passage lived Itche-Meier the stationer, who spent every free moment studying the Bible with his black cat Fraidl sitting in his lap, and had a son called David, a violinist.

I loved these people — the glazier with his family; the widowed cobbler visited at dusk by a string of nocturnal ladies; fat Noah, a small mountain of flesh wobbling about on two tiny sticks, his wife who despised daylight, the three boys I played poker with, the three plump daughters who spent most of their time in my fantasies; and the stationer Itche-Meier, from whom I kept stealing ping-pong balls. Above all I adored David, and passed many pleasant after-school hours on his back step, where my ears became attuned to the autumnal sadness of his strings.

I remember the day a rowdy mob attacked the quiet defenceless panes of the little house with a hail of stones, and then with bricks. It stood its ground, and all through the bombardment, to my astonishment, David resolutely continued playing his violin.

So summer turned to autumn, and autumn was overtaken by winter — a winter which afflicted men’s tongues with a new language of perfidy and violence. Amid the darkness, even the best of us found it hard to find a consoling word, yet there were those who still argued that the war was about to end.

It seemed to me that ‘my’ little house, which I cherished, understood better. It is not good to talk oneself into impossible fictions, so the house, like a frightened snail, receded into itself.

There was no tramstop in front of the little house, yet the afternoon came when a green Number 8 tram nevertheless halted there. Three young Germans, their guns trained, swiftly alighted. After roughing up the inhabitants of the house, they took them all away. It was to be a journey of no return.

That night I was awoken by footsteps, the squeaking and banging of doors opening and closing, and the suppressed voices of a throng of haggard men who had left their sick wives and children around unheated stoves in freezing homes. Stealthily they walked the snow-white paths, and with crowbars and axes they assailed the little house for what timber they could plunder, until nothing remained.

I would often visit this scene of devastation in my dreams, hoping for a sign of life; but to no avail. One night in spring I unexpectedly came upon a tiny green leaf of grief, wet with dew. ‘It’s true,’ it said, ‘there’s nothing left of what once was. But listen — each night they all come back, their souls in white shrouds. I cannot see their faces, but I can hear their voices and their ghostlike steps, as soft as Fraidl’s paws on the prowl. They never tarry; perhaps they still fear for their life even in death, who can tell? Last time they came I begged David to play, to play once again the story of his little house. He apologized. Ashmodai had tossed his violin into the fire. But he said the melody had escaped the flames. Next time, he promised, he would teach me the song.’

Holy Lies

My friend Kuba Litmanowicz, a toolmaker by trade, was a man of enormous physical strength, great loyalty, few words, and deep, shining thoughts. He was also a lover of the sun. His build and his olive skin always reminded me of the Yiddish verses of Moyshe Kulbak:

East of Time

East of Time