- Home

- Jacob Rosenberg

East of Time

East of Time Read online

EAST OF TIME

Jacob G. Rosenberg

JACOB G. ROSENBERG was born in Lodz, Poland, the youngest member of a working-class family. After the Germans occupied Poland he was confined, with his parents, his two sisters and their little girls, to the Lodz Ghetto, from which they were eventually transported to Auschwitz. Except for one sister (who committed suicide a few days later) all the members of his family were gassed on the day of their arrival. He remained in Auschwitz for about two months, then spent the rest of the war in other concentration camps. In 1948 he emigrated to Australia with his wife Esther; their only child, Marcia, was born in Melbourne. Rosenberg’s poems and stories have appeared both in Australia and overseas. He has published three books of poetry in English, as well as three earlier volumes of prose and poetry in Yiddish. This is his second book of prose in English.

ALSO BY JACOB G. ROSENBERG

Poetry and prose in Yiddish

Snow in Spring

Wooden Clogs Shod with Snow

Light — Shadow — Light

Poetry in English

My Father’s Silence

Twilight Whisper

Elegy on Ghetto (video)

Behind the Moon

Prose in English

Lives and Embers

East of Time

Jacob G. Rosenberg

BRANDL & SCHLESINGER

© Jacob G. Rosenberg, 2005

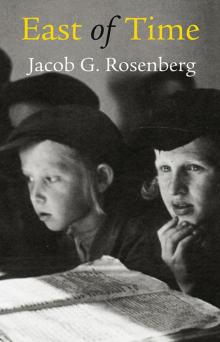

Cover: Talmud students. Trnava, Czechoslovakia, 1937 © Roman Vishniac

Author photo © Shoshi Jacobs

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism, review, or as otherwise permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

First published by Brandl & Schlesinger Pty Ltd in 2005

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Rosenberg, Jacob, 1922–.

East of time.

1st ed.

ISBN 1 876040 66 1

1. Rosenberg, Jacob, 1922–. 2. Jews – Poland – Lodz. 3. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945) – Poland – Personal narratives. 4. World War, 1939–1945 – Personal narratives, Polish. I. Title.

940.5318092

Typeset in 10½ pt Legacy

Book design by András Berkes

For Marcia, with love

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish to express my deep appreciation to my editor, Alex Skovron, who like a biblical scribe has led me through three collections of poetry and now two books of prose. I am convinced that thanks to him the gods of literature are watching over me.

My heartfelt gratitude to Professor Louis Waller and Professor Richard Freadman, and to Alex Miller, for giving so generously of their time, reading the manuscript, and offering valued comments and responses.

I want also to thank Bernard Hirsch for his scriptural counsel.

Finally, I am indebted yet again to my dear Esther, who constantly dispels my often self-imposed disenchantments.

Preface

East of Time is a rendezvous of history and imagination, of realities and dreams, of hopes and disenchantments. The story is set in Łódź (Lodz), city of the waterless river, the Łódka, which in my time consisted largely of black mud from the town’s industrial waste. Thanks to its mighty textile industry, the city was known as the Polish Manchester. My rendezvous spans a period from childhood to early maturity, a period when I witnessed the grand belief in a just new world overtaken, first, by the cataclysmic events of the 1930s, then incarcerated between the walls of the ghetto established in my town by the Germans, and finally silenced at Auschwitz.

The anecdotes, incidents and characters that appear throughout these pages come directly from my memories — although some names have been changed, and occasionally I have succumbed to the storyteller’s prerogative (and delight) in a measure of embellishment, not to say invention. The narrative is broadly if not slavishly chronological, with brief excursions where appropriate into the future or the past. The touchstone of these reminiscences — their informing spirit — is the desire and determination of an entire community to remain human, even at the last frontier of life.

The short verses quoted here and there are the songs and poems of the people of my world — an intimate, inseparable part of the human landscape of the times, and a defiant response to the adversities of daily existence.

As for the many individuals who populate this book, most, with one or two exceptions, are now dead, murdered during those years of darkness. Some readers may question my purpose in summoning up all these names, but the need to recall them is strong within me; perhaps it is the scriptural influence, or maybe the voice of my forefathers, to whom the mentioning of names was a sacred duty.

J.G.R.

Bona Fides

I was born to the east of time, in the city of a waterless river, in a one-room palace. My parents were millionaires: father was a textile weaver of dreams, mother was a spinner. My two sisters and I shuttled between the threads of their colourful yarns.

With the break of dawn my father and mother rushed off to work (if there was work), my sisters to school, and I to the nearby kindergarten. I was always the first one there. Alone in the big playroom, I watched the dance of shadows, touched the terror of emptiness, and listened to the drumming of the loose windowpanes in the wind.

At the age of seven I became a student at the unique Vladimir Medem school, a private establishment owned by an ideology, that of the socialist Bund. But a fee still had to be paid, so father forever went about in second-hand suits and shoes — education for his children took precedence. At the school I was taught Yiddish and Polish, history, geography, mathematics, algebra, astronomy, and (most important) how to be a mensch. I passed well in most subjects but the last, in which my marks were low.

My teachers were mentors by day, librarians at dusk, and camp-leaders during our holidays. I loved them all, especially Miss Joskowicz, a tall blonde who taught us Polish history, which I was very fond of. And although I was attentive to every word that emerged through her wholesome cherry lips, I never quite gained the grades I deserved. My father couldn’t understand why. How could I explain to this straitlaced weaver, with dreams so different from mine, that between me and the subject I adored stood my beautiful teacher’s majestic bosom, for which I was ready to give up not only the Polish kings but the royalty of the whole wide world?

There were no flowers in our secular schoolyard, no greenery in its vicinity. Amid a forest of red chimneys, with their luscious curly grey wigs of smoke, in a rented chain of rooms on the third floor, under a lease of constant eviction, we feasted on magic gardens planted by devoted scribes in the singing pages of our Yiddish books.

My teachers, scholars in their own right, banned from universities for being Jewish, wore battered shoes and tattered shirts in our unheated rooms as they released Prometheus from his shackles, conquered the Sisyphean nightmare, then led us upon excursions to the heights of Kilimanjaro and the depths of the human soul.

Our unemployed fathers, whose days were too long and nights too short to bespeak and plan the glorious world to come, kept the school alive with their meagre earnings. Our down-to-earth mothers, serving hot barley soup for breakfast at break of dawn, hummed with all their heart Yitzhak Katzenelson’s sunset songs:

My sun sinks into flames

On a dying beam;

Such is my hope,

My dream.

And my pale-faced companions with dark storytelling eyes readily confided, ‘In our house, bread

never gets the chance to go stale.’

Bałuty, where we lived, was the poorest quarter in our city. In this world of meek rebellious shoeless cobblers, coatless tailors and coughing miners, we were taught that there is no God. But that one ought to live one’s life as if there is.

My Father

I’m no psychologist, but I would dare to guess that the path leading to a simple man’s mind and heart is a straight one. My father Gershon was no simple man, perhaps because there were too many struggles and disappointments in his formative years. These made him the hopeful doubter, the optimistic pessimist that he was.

At the age of fourteen he was forced to leave his parents’ home, his yeshiva life, the shtetl of his birth, and he arrived unexpected in the big city of the waterless river, where his older brother Avraham had established a textile factory in his dining-room. Father quickly learnt the trade, and after one year was already earning a rouble a week — which was collected for him by his sister-in-law, for ‘safekeeping’.

The year 1905 was one of great proletarian ferment; strikes broke out, barricades were erected. The Russian masses had awoken, and Jewish workers, too, under the banner of the illegal Bund (of which my father was a leader), took to the streets with red flags, songs and placards demanding freedom, justice and better pay.

The ill-advised Tsar answered with bullets, and with persecution and pogroms against the Jews. My father was in the midst of it all. It was the spring of his life, he was young, a smallish but handsome man, with a song in his bones.

O brothers, we are united

Of life and death one band

Arm in arm dedicated

The red flag fast in our hand.

Should a bullet hit you, my true one

A bullet from our foe the hound

I’ll carry you out from the fire

And heal with kisses your wound.

But if you fall in battle, my true one

And the light in your eyes is no more

I’ll enfold you in our flag, the red one

And together we’ll fight our war.

Two years later, in 1907, one evening just before dinner, there was a knock on the door of my father’s unlit room. He opened it, and there they stood: two members of the notorious Ochrana, the Tsarist secret police. ‘Gershon,’ they said, ‘you come with us.’

Gershon was sentenced to life in the freezing snows of Siberia. But the party hadn’t forgotten him. Eighteen months later he escaped, having received false papers that entitled him to enter America. He got as far as Berlin, but here he began to doubt. If people like him started taking off, who would be left to make the revolution?

In 1913, Gershon married my beautiful hardworking mother, Masha. Were they suited? Were they happy? I don’t know. Children, especially when their parents are long dead, like to think that everything in their mother and father’s life together was smooth sailing. But Gershon was too restless a man to be fully satisfied with domestic bliss; he was still much involved in politics and the camaraderie of party life.

Yet when our world crumbled, when our springs arrived in a vortex of snow, and our summers walked about the earth in a mantle of dull dust, Gershon stood fast by his wife. Hand in hand he went with her, through the bleakest tunnel and to its very end, to the night that awaited them there.

My Mother

There was once a man of great piety, very few words, and many good deeds. His name was Aba and he fathered five daughters. One of them was my mother. Though she had a religious upbringing, she married a man who had totally abandoned all religious traditions. At first she still fostered some customs, such as candle-lighting, to which my father did not object; but since he was intellectually dominant, mother gradually fell under his spell. She joined his party, spoke his tongue, sang his songs, and began reading books, lots of books. Did this transformation bring happiness to her life? I don’t know, it’s hard to say — not because her son didn’t often sense her resigned mood, her well-concealed melancholy, but because the phenomenon we call happiness is so difficult to define. In any case, all her qualities — including that of being physically stronger than father, and (because of her skill level) an earner he could never hope to be — made mother an equal partner in my parents’ marriage.

I cannot remember my mother not singing, though again there was a sadness in her voice, a sadness that could transform even a simple folksong into a tender psalm:

Childhood, beautiful childhood years

In my memory forever you’ll stay;

When I think of you my eyes fill with tears,

Oh, how quickly my childhood flew away.

These psalm-songs were my mother’s cocoon, where she could hide, feel safe, and feel whole.

I knew that mother loved her husband deeply, but I doubt if her love was returned in the same measure. There was a disparity in my parents’ life. Mother’s world was her home; father’s home was the world.

Mother was open with her children, especially with my sister Pola. One evening, when Pola was about twenty, mother said to her: ‘You were born at the outbreak of the Great War. When I had you I was quite alone. Father continued with all his activities as if still a bachelor — he often attended long party meetings and discussions, and on a Saturday or Sunday, after an all-day conference, he would go to the cinema with female comrades. I was hurt,’ she confided, ‘though I knew he wasn’t being unfaithful.’

‘How did you know, Mama?’ asked my sister with tears in her eyes. ‘How did you know?’

‘Because when he came back, his lovemaking was always more intense than ever... Though even then,’ mother added in a whisper, ‘he was selfish.’

‘Then why didn’t you leave him?’ her daughter cried.

‘Because I love him with every fibre of my being. Lovemaking, dear child, is not love. Love is much, much more. Much, much more,’ she repeated.

As daylight began to wane, a serenity that almost glowed would settle on mother’s face. Her moist brown eyes would glisten, and though she did not move her lips, I knew that everything in her was singing, singing its way back into her cocoon, where my mother’s darkening horizon could succumb to the music of her inner light:

O little Sabbath candles,

Your flames an everlasting story;

My father’s home,

My people’s glory.

An Incident

One summer, mother and I went for a short vacation on a villager’s farm, about ten kilometres from our city of the waterless river. On a sunny, still afternoon, mother, the most beautiful woman in the whole world (I was six at the time), wearing a pale-blue linen dress trimmed with gilded buttons, spread a chequered red woollen blanket on a lush patch of grass, sprinkled with wildflowers, not far from the farm. As we were about to sit down, a pleasant-looking man — one Mr Wolf, a friend from mother’s younger years who happened to know that we had arrived — came over to say hello.

Mr Wolf had a ruddy face and shiny black hair parted in the middle; he wore white slacks, a navy-blue shirt and a pair of gold-rimmed sunglasses. Uninvited, he stretched himself on the edge of our blanket and, chewing on a blade of grass, began to murmur to mother under his breath. Mother smiled and smiled, but wouldn’t answer him. He turned up again the next day, and the next. On the third day, mother weakened and responded to his murmurs with half-words that I couldn’t understand. When he finally left us, I asked her who this man was and what he wanted. She replied that he was just a wandering pleasure-seeker. What did that mean, I wanted to know. A funny and harmless adventurer, she explained.

Later that afternoon, when we returned to the small room we were renting at the farm, mother asked the farmer for some roses. As she placed them in a vase, I heard her say to herself: ‘The riper the rose, the nastier the bug.’

The following morning we cut short our little holiday. Thinking back, I wonder if it was because my resolute mother feared Mr Wolf... No, I don’t think so. What she probably feared more was herself.

&

nbsp; My Sister Pola

Are we not the rightful heirs of our parents’ virtues and blemishes, the beneficiaries of their spiritual genes? And are we not also infected by the social and political bacteria of our time? My sister Pola was born in the shadow of the Great War, of formidable public upheavals, pogroms, and the Russian Revolution.

At age sixteen, in the city of the waterless river, she joined the KZM, the Communist Union of Youth. Our father, the anti-Communist labour man, was visibly upset. I was present when he spoke to her about the fate of those who fought for her cause, years before Arthur Koestler immortalized N.S. Rubashov in Darkness at Noon. But my mercurial sister refused to be deterred by father’s grim warnings. ‘Anti-Soviet garbage!’ she fired back. She produced from her bag a coloured flyer with a picture of a young, happily smiling Komsomolec, whom she dreamt to emulate. ‘This is the truth about the Soviet Union,’ she shouted triumphantly. ‘Anything else is just Fascist propaganda.’ ‘Who taught you that,’ father asked quietly, ‘your cell leader?’ ‘Yes,’ she replied. ‘In fact, he has just returned from Moscow.’ Father shook his head. ‘Well, my daughter,’ he said, ‘as it is written, you would do well to keep your distance from a fool, so that you don’t learn foolish talk.’

At eighteen, Pola was arrested and sentenced to three years in prison for encouraging the workers of Poznanski’s textile factory to down their tools, and for distributing leaflets with the following text:

O worker, brother, awake, awake,

See how the east has banished the night;

Comrade Stalin has ignited the flame

And restored to glory your right.

But nothing could discourage my doughty sister from her task. When, at her trial, she was asked her religion, she answered resolutely: ‘None!’ Did she have anything to say in her defence, the judge inquired. ‘Yes, your honour. I have been beaten in prison. That’s illegal!’ The judge ordered her taken away; Pola went on screaming, ‘It’s illegal, it’s illegal!’ For her audacity she received from the court policeman two hefty slaps across her face. She bled, mother fainted; but Pola would not be silenced.

East of Time

East of Time